Del Mar’s distant history is a fascinating patchwork of thieves, rats, and canoodling celebrities. Most of the landmarks of that past are gone, but a few hang around, masquerading as undistinguished markers of everyday life. Once exposed, they remind us how far Del Mar has come since its days as a quaint resort town––sometimes not in a great way. "People here tear down houses... but not all of them," says amateur historian Juliana Maxey-Allison, who lives in one of several original homes along 10th Street that still survive from 1885, when the State of California was just 35 years old.

Del Mar was once known as Weed––not for its flora, but for the man who owned most of it: rancher and postmaster William S. Weed. But the reason Del Mar’s citizens are not called Weeders is that Del Mar prefers considering its founding father to be the accused arsonist who first developed the land.

Colonel Jacob Shell Taylor, a 6-foot Texan who claimed to have once been an Indian scout for Buffalo Bill, already owned Rancho Penasquitos and the Stonewall gold mine near Julian. After he heard the railroad was extending southward from Los Angeles, he smelled a second gold mine. In the summer of 1885, he had a depot built (on what is now Stratford Court), and Taylor paid $1,000 in gold for the 338 acres of the town of Weed that lay between the ocean and the train.

A year later, Taylor opened the Casa Del Mar (Sea House) steps away from his depot on 9th Street, on the edge of the bluff between 10th and 11th. The name was borrowed by Ella Loop––the wife of Taylor’s real-estate partner, Theodore Loop––from a poem called "The Fight on Paseo Del Mar."

The 30-room resort boasted two open-air dance halls and a protected swimming area in the ocean, accessible by a stairway, that screened bathers from rip tides and sting rays. With a good low tide, you can still see the stubs of piling from what Taylor called a natatorium on the beach at 10th Street.

Del Mar California

Taylor marketed Del Mar as "the Newport of Southern California," referring to the Rhode Island resort for the rich. Charlie Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino and Marion Davies were among its first visitors.

"It was not Newport," Maxey-Allison says, "but it was that kind of ambition. Huge and popular. You would come out here to breathe fresher air––at the time, it was all about the air because of tuberculosis. There were horses on the beach. You could do pretty much what he said–– almost everything."

Taylor and Loop subdivided the surrounding land and built 14 modest, Mission-style houses for brand-new residents. Each sported four rooms, eight-foot-high ceilings and running water; each was either sold for $600 or rented to hotel staff. Nowadays, the home where Taylor and Loop first drew up their plans for Del Mar, Alvarado House, was moved from 144 10th St. to the garden section of the San Diego Fairgrounds, where it’s opened to the public every summer during the San Diego County Fair.

Unfortunately for Taylor, his dream would last only three years. It was drowned in 1888 by heavy rains that washed out the train tracks, some houses and the foreseeable future for Del Mar tourism.

"Everything was wiped out," Maxey-Allison says. "And this guy had put electric lights and wooden sidewalks in. He really did it up, and it was all gone because of the rain. It was torrential, like what we had this winter, only triple." In 1890, the Casa Del Mar burned to the ground. When Taylor collected the insurance money, many of Del Mar’s 100 or so residents grew suspicious and discovered other mysterious fires associated with Taylor's properties. They sued, and he split for Texas.

Del Mar, California

While many historians implicate Taylor in the fire, the current president of the Del Mar Historical Society cuts him some slack. "He did clear the debris from the burned hotel site and began rebuilding," Larry Brooks says. "However, I believe the reality of the times caused him to rethink. Also, an ex-wife living next door probably did not help."

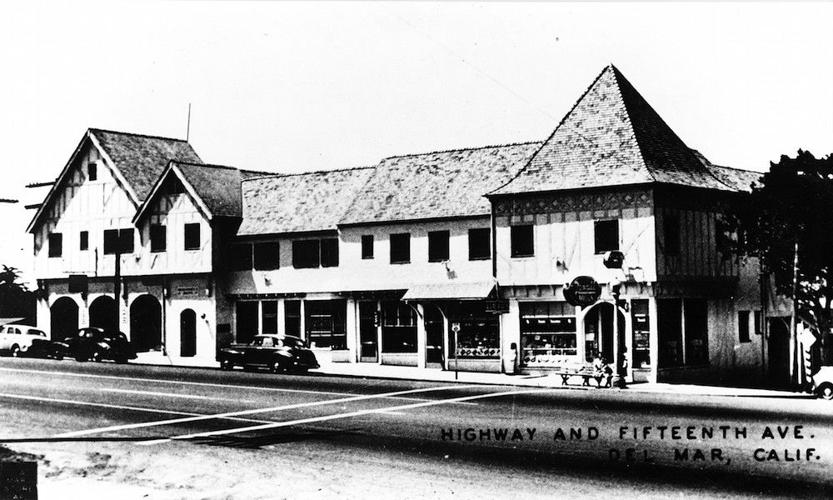

There is no argument that Del Mar fell into decline for more than a decade afterward. But in 1905, it was back in business thanks to the South Coast Land Company, which attempted to follow Taylor’s Del Mar blueprint. The powerful L.A. syndicate, which developed much of San Diego, built Del Mar a new luxury hotel––and a new center of town, where it remains today––at 15th Street between Grand Avenue (now Camino Del Mar) and Coast Boulevard.

With its board-and-stucco motif, the Stratford Inn (renamed the Hotel Del Mar in the 1920s) attempted to evoke Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s historic British hometown, and hosted plenty of its own history. According to Jim Watkins, who built L’Auberge Del Mar from the Hotel Del Mar’s ashes in 1989, the Hotel Del Mar was where one future music superstar got the idea for a major component of his act.

"There was only one grand piano in town, in the castle at the top of the hill, so they brought it down," Watkins says. "But the performer just didn’t feel that the atmosphere was quite right. So there was a candelabra on top of the mantel in the hotel, and Liberace took it off and put it on his piano, and that’s how that started."

The Stratford Inn’s honeymoon cottage still stands at the corner of 15th Street and Ocean Avenue as a private residence, and the building that served as the hotel’s parking garage is now the restaurant Jake’s Del Mar. But the hotel was razed in 1969, a rat-infested shell of its former self. Part of the problem was Interstate 5. When it opened locally in 1967, it rerouted all north-south traffic away from Del Mar.

Del Mar California

"Del Mar had 11 service stations," Watkins says. "It was known as gasoline alley. And suddenly, there was just no more business. And so the mayor asked if I would do an economic analysis and determine what could be done."

Watkins’s first order of business was his 1971 purchase of the former Kockritz Building, a retail center built next door to the Stratford Inn in 1927 that mimicked the hotel’s look. The most prominent building in the village, which hosted a USO outpost during World War II, Stratford Square still stands and Watkins still owns it––although the economy forced him to sell the L’Auberge in 1994.

"There was a junk shop on the corner, a dirty bar on the corner and most of the rest of it was vacant, except for the ladies of the night upstairs," Watkins says. "We were fortunate to bring it back to life."

Also still standing is the original train depot built to bring tourists to the Stratford Inn. The South Coast Land Company relocated it to Coast Boulevard and 17th Street and rebuilt the washed-away tracks on their current location on the bluffs. But trains quit stopping at the Del Mar train station in 1995, once the vastly bigger Solana Beach station opened.

"I think everybody who lived in Del Mar liked being able to go to the train and go anywhere they wanted," says Del Mar Historical Society board member Carolyn Batzler. "It was a charming place, and it was a major loss."

Saved by a consortium of local real-estate developers who now use the building as offices, the depot is known primarily as having been the only passenger train stop between Oceanside and San Diego for decades. Quite strangely, it’s also known for hosting the first public performance of the

Monkees. The Prefab Four, who were unknown at the time since their NBC TV series wouldn’t debut until the following night, performed two songs––their "Papa Gene’s Blues" and a cover of "She’s So Far Out, She’s In"––on the caboose of an L.A.-bound train stopped here on September 11, 1966. It was part of a L.A. radio-station contest whose 400 winners got to ride the train with "the next Beatles."

As far as setting Del Mar on course toward its thriving present, however, one still-standing structure beats all others by considerably more than a nose.

"Del Mar was once a sleepy little town where you’d go to the beach and know everybody," Batzler says. "When the racetrack opened, it started becoming what it is today––a destination for people all over the world."

Del Mar California

Looking much as it did when it opened in 1937 at the height of the Great Depression, the racetrack was the passion project of horseracing fanatic Bing Crosby. After the Del Mar Fairgrounds were built with a $25,000 land grant from the State Department of Fairs & Exposition, Crosby, who stabled his own racehorse at his nearby Rancho Santa Fe home, put up $600,000 in personal loans against his own life insurance to will his dream into reality.

Crosby and his partner, character actor Pat O’Brien, invited every celebrity they rubbed shoulders with in Hollywood to come down for racing and swanky afterparties. Regular sightings for Del Mar residents included Betty Grable, Jimmy Durante and Lucy and Desi Arnaz, all of whom swam in the ocean and ate in local restaurants during their stays at the Hotel Del Mar or in oceanfront vacation rentals. Durante, Del Mar’s honorary mayor, got the road leading into the racetrack named after him, while Desi Arnaz lived in Del Mar following his famous divorce.

In 1938, Crosby used his weekly NBC radio show––then the nation’s most popular––to broadcast a match race he arranged between South American champ Ligaroti and America’s best-known racehorse, Seabiscuit, who won the thrilling head-to-head battle.

"It put Del Mar on the map," Watkins says. "And [the racetrack] is still on the map––so is Del Mar."

(0) comments

We welcome your comments

Log In

Post a comment as Guest

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.